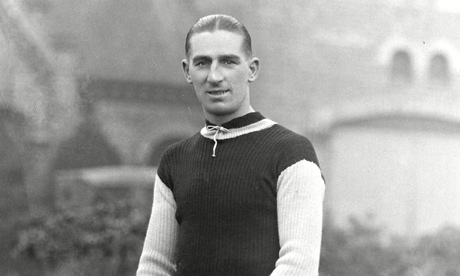

“I was brought up to play hard and saw nothing wrong with an honest-to-goodness shoulder charge,” Frank Barson once said, emphatically playing things down. In fact he was brought up to be a blacksmith and, hardened by all that exposure to fire and molten metal, grew into one of the meanest and toughest defenders in the history of the English game. When Barson lined up against them an honest-to-goodness shoulder charge was the very least of his opponents’ worries.

Born in Sheffield, Barson’s professional career started at Barnsley where, in a game against Grimsby in February 1914, he accidentally (or that’s what it said in the local newspaper) collided with the referee, a Mr Bamlett of Gateshead, knocking him unconscious. He continued to give match officials – and, indeed, his own clubs – no end of headaches thereafter.

In so doing he made very few friends at the Football Association, then a straight-laced organisation that took unkindly to casual violence on the field of play. He was to become the first player to be charged retrospectively for misconduct – after a trademark challenge (they used to call it “The Barson Barge”) on Manchester City’s Sam Cowan in the 1926 FA Cup semi-final – and have his career effectively ended when a sending-off led to an unusually harsh seven-month ban.

Barson joined Aston Villa in 1919 for £2,850 after falling out with Barnsley over travel expenses. He stayed for three years, becoming increasingly unpopular with the Villa hierarchy, principally because of his refusal to move to Birmingham from his home in Grimesthorpe, on the outskirts of Sheffield. He had business interests there and a circle of close friends that included Lawrence and William Fowler, notorious leaders of the city’s then thriving gang culture (on the day Sheffield United beat Cardiff in the 1925 FA Cup final the Fowlers got into an argument over a barmaid with a chap called William Plommer and ended up killing him, an offence for which both were hanged. They traded letters with Barson from prison while they awaited their fates).

In 1920 he won the FA Cup with Villa, who beat Huddersfield 1-0 at Stamford Bridge, a game in which he earned the unlikely distinction of receiving a warning as to his conduct by the referee, Jack Howcroft, before it had even kicked off. “The first wrong move you make, Barson, off you go,” Howcroft said. There would be no wrong moves.

Even that trophy did not improve his standing in the Villa boardroom and, when he missed the first game of the following season after mistiming his commute, they suspended him for a fortnight and gave him a month to move to Birmingham. He refused. (The irony here is that after his playing career ended he did indeed move to Birmingham and at the time of his death was living a short walk from Villa Park). Villa suspended him again in March 1922, for inviting a friend into the dressing room at Liverpool and refusing to apologise for it.

He was good enough, though, to be worth a bit of hassle. The book Aston Villa: A Complete Record (not to be confused with the book Aston Villa: The Complete Record, which is an entirely different tome by different authors published 22 years later) says that “despite several brushes with authority, Barson was a truly great centre-half, a fierce tackler and dominant in the air … he revitalised a flagging Villa team. His dynamic personality brought the best out of the players.”

He was made captain and scored a celebrated 30-yard header against Sheffield United. He was particularly skilful with his head and once, in a match against Tottenham, dribbled the ball from one end to the other without once using his feet. It was estimated that he headed the ball 86 times during the run, which ended within yards of the Spurs goal.

“There isn’t a centre-half anywhere in the land who can break up an attack so skilfully; who can pull a high ball to the carpet and keep it there; who can nod a ball down to a colleague’s toe with his head; who can shoot with such amazing force and accuracy; or who can do such foolish little tricks in the temper-displaying line as this player,” read one profile, written by someone bylined enigmatically as “an outside right”. “There’s the rub. Frank isn’t in good favour with the high authorities simply because his name is for ever associated with rough play, yet you can take my word for it that he is never a man to go out of his way deliberately to crock a player. Give Frank a rough and tumble and he’ll be delighted, for the simple reason that a trial of real strength is to him a breath of ozone. It is a tonic, just as a fight is to an Irishman or an argument to a Scot.”

After that incident on Merseyside Barson submitted a transfer request, and in the summer of 1922 he joined Manchester United, then in the Second Division, for £5,000. He was immediately named captain and, despite a string of injuries, became enormously popular – though, as the Times once aptly put it, he was “not loved by any but members of his own crowd”.

“Opponents have got so tired of his never-ceasing wrong-doing that there is a movement afoot to send a petition to the authorities in order to prevent the player from crocking others,” one paper reported, early in 1925. That campaign, apparently organised by the Chelsea squad, came to nought and at the end of that season United finished runners-up to Leicester in the Second Division (10 points and three places ahead of Chelsea) to earn promotion to the top flight.

Barson had a unique reason to celebrate that achievement. According to the terms of his contract with United, if the club were to secure promotion in any of the three seasons after his arrival, they would immediately and without delay give him a pub. So at the end of the 1924-25 season Barson was handed the keys to the George & Dragon in Ardwick. On his opening night the bar was so busy, with many fans seeking the attention of Barson himself, that within an hour he told the barman he could keep the place and fled, never to return.

There were other bonuses. “Jack Smith, a much underrated player before the last war, told me the story of how, when Barson walked into the United dressing room, he would put a hand on to a shelf in search of a package before he took his coat off,” the long-time Manchester City scout Harry Godwin once said. “One day there was no package and he said to the trainer, ‘Where’s the doins? I’m not taking my bloody coat off til I get it!’”

Again he was worth the hassle. After United beat Sunderland to reach the 1926 FA Cup quarter-finals, the Guardian crowed that he had been “a commanding figure”. “He held the side together at a critical time and set an example of bold tackling, well-judged passing and not a little daring that was of incalculable value,” we wrote.

But eventually age and injury slowed him down. Towards the start of the 1927-28 season he suffered a spine injury, which kept him out for several months and after finally returning to fitness he broke his nose in his first game back. At its end United made him available on a free transfer, which despite the injuries was considered by the Dundee Evening Telegraph “one of the greatest surprises of the football season in England”. “If Barson is now recovered from his troubles there will be many clubs only too ready to sign him,” they wrote. “Frank has always been a much criticised player but no one can doubt his great ability. He is credited by those competent to judge with being the best centre-half since the war.”

Perhaps he had not fully recovered from his troubles because, when the move came, it was to Third Division Watford, who that summer also signed his United team-mates Billy Chapman and Tommy Barnett. The latter went on to score 163 times for the club in league and cup, a tally bettered in its history only by Luther Blissett, but Barson’s time at Vicarage Road was to be briefer and much less glorious.

A few games into it, in September 1928, during a 6-2 home defeat against Fulham, he was adjudged to have kicked Jimmy Temple and was sent off. He refused, arguing his case with the referee for a while before reluctantly trudging from the field.

Barson may well have become famous for a predilection for menace and violence but his disciplinary record had always been considerably better than his reputation. “I felt I had a bad game if I was not booed but I never punched or butted anybody,” he said in 1965. “Players today are stupid. Cruder. They do things openly and ask to be sent off. We did it without being seen half the time.”

When he did enrage a referee it was most frequently because of things he had said rather than what he had done. “Though one of the greatest half-backs in football, Barson has a reputation for impulsiveness and does not always keep a guard upon his tongue,” the Yorkshire Evening Post once wrote, summing the situation up rather nicely.

Now, it was as if the FA had bottled up a career’s worth of enmity and finally got an excuse to pull the cork. They had picked on him a little bit before: in the 1926 FA Cup semi-final the referee had deemed his shoulder charge on Cowan worthy of no more than a free-kick but a couple of watching FA councillors started disciplinary proceedings against him anyway, a move without precedent in English football, and then banned him for two months.

Those same FA councillors had full control over England team selection and, despite his reliable excellence, Barson’s international career stalled after a single cap, against Wales at Highbury in 1920 (it was England’s first defeat by the Welsh since 1882; Billy Meredith was Wales’ inspiration, playing at outside-right at the age of 44).

“For years Barson was without question England’s best pivot, yet the selectors consistently passed him over,” reported the Daily Worker in 1930. “Boss sport being what it is, it was more than a rumour that it was not only his vigorous play that kept Barson from a heap of caps: that someone behind the scenes in the Football Association had blackballed him.”

At the time of his offence against Fulham, the FA was developing a taste for lengthy bans. A year previously South Shields’ Cyril Hunter, in a Second Division match against Middlesbrough, had put in a display of such consistent brutality that by the end, according to the local paper, “the Middlesbrough dressing room was like a field ambulance station”. He was banned until the end of the following season, still a British record.

Barson’s offence had been much less clearcut. Indeed, many observers thought it unworthy of even a sending-off. Nevertheless, the FA suspended him for seven months, which effectively – given that it took him to the end of the season – meant he could not play again for nearly a year.

“The most I ever dreamed of was a month’s suspension,” the player said at the time. “I have a wife and three children and am faced with the prospect of seven months without a livelihood.” Barson insisted that Temple was to blame, having grabbed him by the leg and refused to let go. “In trying to free myself the referee apparently thought I was trying to kick Temple,” he claimed.

Barson’s suspension caused considerable controversy in Watford, with the club’s chairman, John Kilby, labelling it “most unjust” and the manager, Fred Pagnam, insisting that “the club are absolutely astounded at the sentence and so are the club’s supporters in the town”.

Watford’s fans were so astounded that they organised a petition demanding the ban be reconsidered and, after 4,850 people signed it, the mayor, Alderman T Rushton, took it to the headquarters of the Football Association. “I have not signed the petition myself but I support it and agree with it,” said Mr Rushton, who had been at the Fulham game, before he set off for London. “My view is that Temple caught hold of Barson’s leg and, as far as I could see, Barson was endeavouring to get his leg released when the referee caused the stoppage and ordered him off the field. I did not see Barson kick Temple. The spectators were shouting a good deal and the players were rather rough, perhaps on that account. Fulham are rather keen – too keen, I think – in trying to regain a position in the Second Division.”

And this is where the tale becomes more extraordinary still for, though Rushton took the petition to the FA, nobody ever read it or even officially received it because, once the mayor had been told about all the nasty stuff the FA had in the player’s file, he asked them to burn it.

Frederick Wall, the FA secretary, later explained what transpired. “On arriving at the FA offices the mayor stated he had come to present a petition on behalf of Barson and asked if he might read it,” he said. “I asked whether the mayor had read the referee’s report with reference to Barson. He said he had not, so I showed him the original report. I asked, ‘Do you know anything of Barson’s history as a football player?’ The mayor replied he did not. So I read to him information showing that we, the FA, had had to consider numerous reports of Barson’s misconduct on the field, that he had been suspended on three previous occasions, once for one month and twice for two months. The Mayor asked me to destroy the petition. I destroyed it with his knowledge and in his presence. It was burned in his presence.”

According to the referee, Barson had deliberately kicked Temple and, having been sent off, refused to leave the field for some minutes and then threatened the referee before doing so. Some form of punishment for this seemed inevitable but the severity of his punishment and the justification for it appear puzzling.

Wall referred to three previous suspensions. The one-month ban followed a sending-off in the first round of the 1914-15 FA Cup, 14 years earlier. It may seem lengthy but Barson was one of four players to get such a punishment that weekend alone. Of the two-month bans, one apparently followed a brawl in a pre-season friendly against Birmingham City in 1911 and the other followed that 1926 semi-final and anyway covered the entirely irrelevant period from 3 May, two days after United’s last game of the season, until the start of July. Clearly Barson was no angel, but his heinous disciplinary record essentially amounted to one fabricated suspension in 14 years.

The Watford supporters’ club launched a new petition, this time collecting more than 15,000 signatures, but still the FA was unmoved. “The signatories of the petition cannot know the facts of the case,” they sniffed. “We therefore must decline to reopen the matter.” Barson served his suspension, never playing for Watford again (instead he managed the King William IV pub on Watford High Street for a while), before joining Hartlepool and then Wigan Borough, who found his wages such a stretch that they went out of business 18 months later.

Perhaps it could be argued that Barson’s ban was not long enough: his last ever appearance in the Football League came on Boxing Day 1930, by which time he was 40, and he ended on a suitably brutal note. In the 83rd minute of a match against Accrington Stanley he jumped on an opponent and then swore at the referee after he was sent off. The disciplinary commission that adjudicated the matter reported that they were “satisfied the conduct of both teams in the match did not reflect any credit on the players concerned”.

Barson went into coaching, including spells with Villa’s juniors and seniors and a short period there as caretaker manager, and died at the age of 77 in 1968. “A strong, commanding and forceful centre-half, his vigorous play so incensed the crowds that the moment he stepped on the pitch he was greeted with cries of ‘Dirty Barson!’ wrote the Guardian in a short obituary. “Yet it might have been a case of giving a dog a bad name. Apart from the strength of his play he had few equals – and there are certainly none today – in the matter of heading the ball. To see Barson stand in the centre of the field and direct a full-blooded clearance with his head to either wing was a sight indeed.” It was just a pity that nobody at the Football Association appreciated it.

As it happened, three months after Villa signed Barson in October 1919 they brought in another, younger centre-back who was to become just as memorable. If Barson was notorious for his violence on the pitch, however, the man who eventually took his place in the first XI, Tommy Ball, was to be remembered for his violent end off it. But that is another story.

The forgotten story of Tommy Ball will be published on Wednesday.