Last year may have passed without the sight of sporting heroes parading in open-top buses through central London, but the syndrome such events came to represent evidently remains intact. If the 5-0 thrashing of England's cricketers in the Ashes series contains a meaning that goes beyond the familiar can't-bat-can't-bowl-can't-field diagnosis, it is to be found in the descent into the abyss that now seems almost traditional for English sportsmen and women following their moments of ultimate triumph.

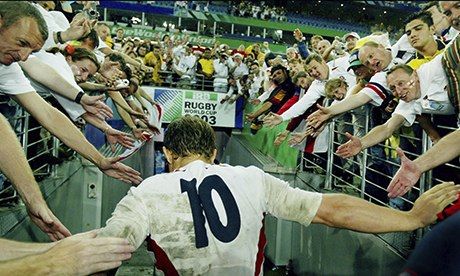

We remember how the euphoric parade of Clive Woodward's rugby players after the World Cup victory of 2003 was followed by rows that resulted in the head coach's removal the following season. The subsequent decline into mediocrity culminated in the dwarf-throwing debacle in New Zealand in 2011, and the damage done during those eight years is still being repaired.

The cricketers who snatched a desperately thrilling last-gasp Ashes victory at home in 2005 also made their way in triumph to spray champagne under Nelson's Column before at least one of them, so the story goes, recycled it in the prime minister's back garden. Eighteen months later, stripped of all virtue, they were slaughtered in the return series, surrendering with barely a whimper.

When Alastair Cook's party set off for Australia in November it was barely two years since, under Andrew Strauss, they had made it to the top of the international Test rankings. This, we were being told, was a team who had not just pitched camp at the summit of the world game but were about to take up permanent residence on that sun-washed plateau. Almost immediately they fell to successive series defeats at the hands of Pakistan and South Africa, costing Strauss his job. Cook cheered everyone up by leading the team to a first series victory in India in almost 30 years and then retaining the Ashes at home last summer. Yet now, six months after their notorious celebrations on the Oval turf, Cook and his team-mates find themselves at what appears to be a new low in the public's estimation.

Being whitewashed is forgiveable, but for many observers the manner of their defeat provoked feelings of distaste. Losing Jonathan Trott to depression was bad luck, although it seems strange that no one in the management spotted the signs before the party was selected. The departure of Graeme Swann, however, summed up everything that had gone rotten: a player who had been one of the keystones of the side suddenly opting to abandon ship and breaking the news in his newspaper column rather than allowing the management to make the announcement.

Instead of staying on, accepting the imminent decision to drop him, making himself useful off the pitch and helping to sustain what remained of the team's morale by encouraging the younger players, he made his squalid exit, leaving a nasty and ineradicable stain on what had been a fine Test career. The incident appeared to expose a seam of venality and selfishness that are far from unique to Swann and must surely have been among the contributing factors to the team's disintegration. As many observed, a footballer walking out of a World Cup squad would have been hung, drawn and quartered, yet former Test players queued up to mumble their excuses for his behaviour.

Success in 1966, in hugely favourable conditions, is the event from which England's football team have never recovered, and against which all their subsequent failures have been so relentlessly judged. Even France, having won it in 1998, went on to capture the European title two years later and reached the world final in 2006. This year, at least, England will travel to Brazil accompanied by a sense of realism; it has taken that long for the hangover to subside.

Sustaining success is a problem for England in individual as well as team sports. In the last 40 years five Englishmen – James Hunt, Nigel Mansell, Damon Hill, Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button – have won the Formula One world championship. None managed to win it a second time. During those same decades Michael Schumacher won seven, Alain Prost and Sebastian Vettel four apiece, Niki Lauda and Nelson Piquet three each.

In 2012 Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the Tour de France, secured a gold medal in the London Olympics and was knighted for his efforts. A year later he barely made it to half-distance in the Giro d'Italia, failed to defend his Tour title – or support his team-mate Chris Froome in the race – after injuring his knee, and was the first British rider to drop out of the world championship road race in Florence, setting the example for an abysmal performance that saw none of the team reach the finish line.

Not everyone can be like Jonny Wilkinson, whose profound humility and ironclad sense of vocation survived not just fame but a horrible succession of injuries, or like Mark Cavendish, whose fierce appetite for continued success is perhaps fuelled by the knowledge that he can never cross the Tour's finish line in Paris wearing the yellow jersey. But they are the exceptions among modern English- (or Manx-) born champions, whose willingness to rest on their laurels may have its roots in a post-imperial arrogance and laziness, buried deep in the collective subconscious. Or an assumption, originating when the Beatles conquered the world in the 1960s, of a cultural superiority that meant we only needed to turn up to show that we were the best, a delusion encouraged by print and broadcast media avid for success and building up expectations to ludicrous heights.

The biggest of all the open-top parades came shortly after the end of the London 2012 Games, when the winners of Britain's 185 medals in the Olympics and Paralympics took their turn to soak up the applause from the Mansion House to the Mall. Thoroughly deserved it certainly was, but on past form you would have to fear for their fortunes in Rio in two years' time. There will be no home advantage, of course, but even so it would not be a great surprise to see Britain's athletes slip down the medals table to a position closer to the achievements of the pre-lottery funding era.

It will be interesting to see how Andy Murray, another hero of the golden year of 2012, progresses in the wake of his even greater triumph at Wimbledon last summer. Perhaps he will refuse to allow that to become the deed by which he is remembered and can buck the trend by turning the winning of major tournaments into a habit. But then, he isn't English.